If you’ve been following the stock market at all, you’ve no doubt noticed a strange contradiction.

The world is in shambles. There’s a virus on the loose that’s disrupted the entire supply chain. Businesses have lost trillions of dollars. Unemployment is at all time highs.

And… the stock market is booming?

WTF?

I don’t fully understand it either. Which is why I’ve spent the last month brushing off my Economics degree, searching for inside scoop from my job in Finance, and trying to piece together this complex economic puzzle.

And I think I’ve finally figured it all out.

Today’s post will peel back the curtain on the government’s multi-trillion dollar stimulus packages. More importantly, it will try to decipher what this all means for average investors like you and I, and how we can protect our wealth in these uncertain times.

*Note: I’m trying to keep this as fact based as possible, but some of it requires my interpretation/opinion. And parts are intentionally oversimplified, because sometimes that’s what it takes to piece together the big picture. Nothing here is investment advice.

First thing’s first. Who the heck is The Fed?

In 1913, Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order that created a new branch of government. The Federal Reserve. At first, “The Fed” didn’t do a whole lot.

In fact, The Fed’s responsibilities didn’t really ramp up until 1977, when Congress ordered The Fed to operate under what’s now referred to as their “Dual Mandate.”

No, not that duel. Dual as in, two.

Specifically, The Fed was tasked with two important goals:

- Low unemployment.

- Stable inflation.

In other words, Congress said, “Hey Fed, no big deal, but would you mind monitoring the most complex market in the world for us? K Thx.”

Fast forward to 2008

Banks got wild with their lending, and people began defaulting on loans left and right. The economy was collapsing.

The Fed immediately sees the problem. With massive banks on the verge of collapse, low unemployment (The Fed’s Goal #1) isn’t looking so hot.

And there’s a new problem, too.

Because the economy is so bad, banks aren’t lending. Half of them are on the verge of collapse themselves, and the other half aren’t making loans because they’re too worried those loans won’t get paid back.

With banks not lending:

- People aren’t investing as much.

- People aren’t spending as much.

- Housing prices are plummeting.

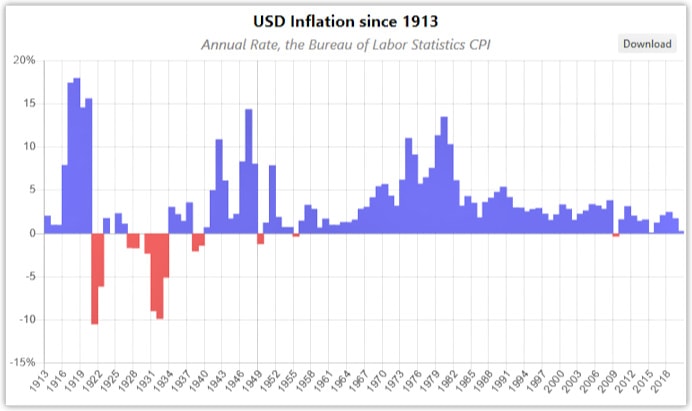

All these things lead to falling prices, aka deflation. Not good.

In fact, deflation is actually the exact opposite of the “stable inflation” that The Fed wants to see. (Goal #2)

With unemployment and inflation both in trouble, alarm bells start ringing at The Fed. This is what they were specifically mandated to control back in 1977, so they realize they have to do something.

They come up with an idea that has worked in the past, at very small scales. They will inject money into the banking system.

They hope banks having more money will do two things:

- Keep banks from failing and keep the economy from collapsing. (Which supports The Fed’s goal of low unemployment)

- Get banks to start lending money again. (Which should help stabilize inflation)

Sounds great! But where’s this money going to come from? And how much is needed?

The Fed’s “Money Printing” Explained

In a normal operating environment, the government issues lots of bonds. These bonds support government spending.

Imagine Uncle Sam wants to create a new highway that costs $100 million. So, he issues a government bond. He collects $100 million from investors and promises to pay those investors interest over time.

As it so happens, some of the biggest investors into government bonds are big banks.

In our example, imagine Bank of America hands Uncle Sam a $100 million dollar bill. Uncle Sam now has the $100 million in cash, and Bank of America now has a government bond worth $100 million, but no cash.

Then 2008 hits. Bank of America is in trouble, and The Fed decides Bank of America needs that cash.

So for The Fed to inject money into the banking system, they can simply trade Uncle Sam’s cash for government bonds already on the market.

And that’s what they did. Started in 2008, The Fed bought about $4 trillion of government bonds. Uncle Sam gave up $4 trillion of its cash, and the banks got $4 trillion worth of cash.

The Fed called this strategy Quantitative Easing. The public called it “printing money.”

What’s the risk?

The most immediate risk of this strategy is inflation.

When you introduce $4 trillion new dollars into the economy and people start spending that money on the same number of houses, groceries, etc. then the price of those goods could potentially skyrocket.

I remember this reaction vividly. Once people saw The Fed carry out its plans, everyone got terrified. $4 trillion of “new money” into the economy was unprecedented!

Everyone imagined we’d soon be carrying around our cash in wheelbarrows like a hyper-inflation Germany.

Except that never happened. In fact, since 2008, inflation has only averaged about 1.5% per year.

Wait, why hasn’t the money printing led to inflation?

Because things didn’t go exactly as planned.

I said before that The Fed hoped the money injection would:

1. Keep banks from failing and keep the economy from collapsing.

Result: Success!

After The Fed announced their plans, the banking system didn’t collapse, and the stock market began 12 year upward march to new all time highs.

2. Get banks to start lending money again.

Result: Ehhh… didn’t go as planned.

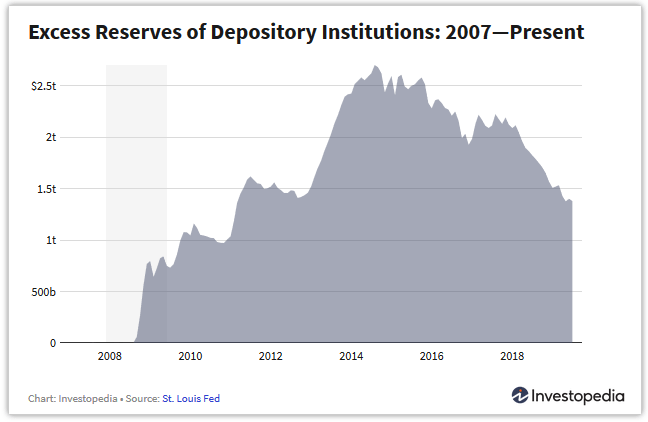

Once the new money got injected into the banking system, the banks did not lend it out like The Fed had hoped.

Instead, most banks held that money as “excess reserves.” In other words, instead of lending it out, the banks used the money to improve their financial security by keeping extra cash or making extra investments.

In my opinion, THIS is why we haven’t seen the hyperinflation that so many people expected. The assumption that printed money leads to inflation only comes true if that new money enters the economy.

But the “printed” money never really entered the economy. Only a fraction of it got lent out, which is probably responsible for the modest 1.5% per year inflation we’ve seen. The rest of the money just sits on the bank’s balance sheets.

The most obvious impact of this extra cash on the bank’s balance sheets are that banks are now safer and richer than before. But, there’s a subtler effect, too.

How money printing boosts stock prices, and what that means…

Economists agree that money printing/quantitative easing also boosts stock prices, for a number of different reasons.

This creates a tricky situation for The Fed, too.

While the new money didn’t get loaned out as planned, it did help lift stock prices. In a way, The Fed now accidentally feels responsible for the new price of the stock market.

Last year, I attended a lecture from a PhD economist who was good academic friends with the 2014-2018 chair of The Fed, Janet Yellen.

Safe to say, this dude knew his stuff.

He proposed that because of the increase in stock price in response to The Fed’s quantitative easing, The Fed now indirectly “owns” the stock market growth. Because of this, he said that in addition to The Fed’s first mandate (low unemployment) and second mandate (stable inflation) The Fed is now acting under a self-imposed “Third Mandate” – stable stock market prices.

He makes a compelling case. Since 2008, any time the stock market begins to fall, The Fed reacts accordingly. Whether it’s an adjustment to interest rates or additional quantitative easing, the trend has been clear:

When the stock market falls, The Fed acts to fix it.

Quantitative Easing 2020 – Coronavirus Edition

When COVID-19 decimated the U.S. economy in early 2020 and stocks started tanking, surprise surprise… The Fed stepped in.

At first, it was an emergency quantitative easing package, this time to the tune of “only” $700 billion. By the end of the year, The Fed is expected to buy another $3.5 trillion worth of bonds. (Aka… print $3.5 trillion dollars.)

No question that these actions by The Fed have propped up the market, despite a horrible pandemic and global shutdown. Which goes a long way in explaining the confusing screenshot posted earlier.

(You’ll also notice the newest stimulus bills includes things like $2 trillion of direct loans to small businesses and aid to hospitals, and even direct stimulus checks to individuals. I suspect this is due to the 2008 stimulus never fully reaching its target audience.)

How long can this game last?

If you’re like most people, at this point you’re wondering how long this can last.

Surely, the government is going to run out of money eventually, right? Won’t the house of cards come crashing down?

The startling answer is… this could go on forever. At least theoretically.

As the theory goes, this problem of money printing can be solved in two main ways.

- The Fed could start reissuing the bonds they purchased. In this scenario, investors would give The Fed money for the bonds, which would return the amount of money in circulation back to normal.

- The Economy could grow its way out of the problem. During World Way II, the U.S. massively expanded debt levels, and our government never really paid it back. Our GDP just grew until the debt payments were so small (relatively) that it didn’t matter.

If I’m being honest, both seem a little unlikely at this point. The economy was strong from 2015 to 2020, and The Fed never took the opportunity to reduce the money supply. And our debt levels are far higher than even WWII levels.

But even those two big scary truths might not matter.

Why? Because ever since we left the gold standard in the 1970s, our money has been “fiat” money. This means it’s backed by nothing more than people’s faith in the system.

And the way I see it, people will keep having faith in that system so long as US Government Bonds are still considered the safest investment in the world. And that will probably keep happening as long as:

- The U.S. remains the world’s superpower

- The U.S. keeps the strongest military in the world

- The Fed keeps stepping in to keep the system in check.

So, how do you and I invest to protect ourselves?

Interestingly, this post leads to an anti-climactic conclusion.

If you want to grow your wealth, none of this changes the best way to do that.

In a world where The Fed continues to prop up stock market prices at the risk of inflation, the riskiest thing you could do would be to not invest your money.

If inflation hits, it’s cash that gets destroyed.

Stocks are protected from inflation, because company earnings typically rise at the rate of inflation.

The only major risk here is a collapse of the entire system. While that still seems unlikely, if you’re truly worried about it, then you could consider shifting your allocation towards a slightly higher percentage of international index funds. If you’re really, really worried about, then take a small percentage of your net worth and invest into cryptocurrency or gold.

For me, this means to just keep on truckin’ with my general three fund portfolio while putting a 1-2% hedge into cryptocurrency. In the future, I may consider a similar amount of gold. I’d also previously decided to increase international index funds to 10% of my portfolio, and I’m still working towards that goal.

Note: This analysis is my opinion. I am not a professional, and nothing in this article should be considered financial advice. You should always make your own investment decisions.

Related Articles:

Great article! Perfectly explained this topic in a way I actually understood.

Awesome, glad it was helpful, Nolan.

The returns on International funds has been really poor for quite some time, and it’s really optimistic to see that changing anytime soon.

“Diversification is more about admitting to yourself that you have no idea which asset class or strategy will do the best in the future.” -Ben Carlson

This is one of your best articles to date. Thank you

Thanks, Greg!

Sorry for this bit of an off-topic rant, although it is central to the issues in the economy and stock market today: 2020 has really dismayed me. I didn’t like the overreaction to the virus, there was no need to shut everything down. You could argue certain localized shut downs may have been necessary (New York City, other population centers for example), but it’s too late now and this self-inflicted wound will hamper our economy for years to come. All we should have done as a whole was protect the elderly, aka the most at risk, by encouraging them to limit interactions, secure nursing homes and advise other citizens to take common sense precautions. The data shows that you are at very low risk of complications if you’re under 50 (I’d even push that to 60 in some cases, unless you have other underlying conditions). This group is the bulk of the working population.

It will be interesting to see if the Fed keeps propping everything up. It’s so far committed now that I think the only choice would be to keep doing so.

Only true if you have a proper functioning health system, which most of the US does not have access to

In October 2020, let’s use hindsight to review whether we should have shut things down. USA; no shutdown, hundreds of thousands of dead people, mass unemployment, economy staggering along supported by trillions of USD to support things. New Zealand; 6 weeks of shutdown, 22 people dead, trivial unemployment, less than NZ$53 bn of stimulus applied. Increasing data shows that lots of people get covid twice and many are looking likely to have long-term consequent health problems. With hindsight, the whole world should have done a SIMULTANEOUS PROPER 6-week shutdown (not allowed to mingle, only allowed to travel for food) and this whole pandemic would have been a non-event. SARS and MERS were pretty similar to covid but the impacted countries did proper shutdowns and the problems didn’t blow out to be worldwide. I suspect Brian lives in USA and is subjected to the ongoing Trumpwashing.

Hey MMW, thanks for the article. I really appreciate the way you explain very complex systems and processes in simple ways that are easy to understand.

I also appreciated reading your interpretation of why we saw little inflation after the initial quantitative easing that occurred in response to the Great Recession of 2008. You said that banks decided to hold most of this money as excess reserves instead of lending. I hadn’t heard this before, and I’d be interested to learn more about it. It does seem like QUITE a lot of cash to be holding on to just for reserves. Why not invest it somewhere else?

Richard Duncan claims that the reason we didn’t see hyperinflation from that QE was because of globalization. Instead of staying within the US system, this money was flowing into foreign countries. Many Asian countries like Japan, China, etc seem to be common countries mentioned. Japan experienced hyperinflation several decades ago from this (not specifically from the most recently mentioned QE), but I believe a lot of capital has been flowing into China.

If you haven’t heard this perspective, here’s an interview that Robert Kiyosaki has with Richard Duncan that I’d recommend:

Good article. Based on the Fed intervention since 2008 to keep the Stock market and the Economy

in general propped up, Social Security deficit will never exist in the future.

MMW, good article. You’ve explained things well in a simple, efficient manner. In your analysis did you consider if stock buybacks indirectly funded with Fed liquidity had any impact on the stock market and economy?

IMO, that’s for sure a factor. It’s the more detailed explanation for why the Fed feels like they “own” the recent growth of the stock market. And why they’ve been acting to protect it accordingly.

I get the point of Fed printing money and buying bonds, but I don’t get how exactly it reaches the stock market. Are banks and other financial intermediaries selling their bonds to Fed and using that money to buy stocks? Is there any evidence of this?